16 Oct 0-4 shots from a different perspective

Why we should NOT get too exclusive when talking about first four shots?

In the last few years, 0-4 shots theory made a great impact in the world of tennis, and many of us coaches accepted it as valuable information. I personally respect the theory, it helps me to communicate better with the players about the importance of serve and return, and it certainly represents an important part of my practice routine.

However, tennis is a very complex game that stretches beyond numbers, in which many different elements have to be in place in order to perform at your best.

The first idea behind this article is to challenge the 0-4 theory from the angle of the game that cannot be read from numbers. Secondly, by analysing the latest data samples from the best players in the world, we extracted some additional significant points that will help you understand the complete picture. Finally, my main intention was to challenge the theory mostly because of the misconceptions headed towards the practice court, according to which endless “grinding” and consistency are seen as a waste of time.

One of the first statistical analyses of rally length in tennis was made in 2015 Australian Open by IBM. They found out that 70% of the total points in a single tennis match were played under 0-4 shots, 20% under 5-8, while rally was longer than 9 shots in only 10% of the points. In other words, in 7 out of 10 points, each player touched the ball maximum two times.

The history of 0-4 dates far back into the 1980s and 1990s, with the main protagonists like Navratilova, McEnroe, Becker, Edberg, Sampras who built their winning games on short points such as serve and volley, much more than the players do today. It was surely a very important element of the game back then, although perhaps it wasn’t discussed that much. After 2015, more and more data started to appear, and some of the tennis analysts began pointing out the first four shots as a place where the crucial battle for winning the match takes place.

In cooperation with Tennis Stat, a French tennis analytics company, we did a research on the world’s best players and collected the data that is specifically targeted towards the rally length. The official documents made by Tennis Stat are included in the text. Here are some of the most important arguments based on the latest data, but also based on the coaching perspective with some facts obtained by reading between the numbers.

1. 30-35% OF THE TOTAL POINTS IS A BIG DEAL

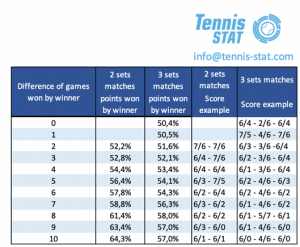

When we talk about the ratio between short and long rallies (which is 65-70% of 0-4 shots and 30-35% of 5+ shots), we need to keep in mind the margins between the victory and defeat in a tennis match. From the data below, you can see that the difference between winning and losing a match is much smaller than we sometimes think. For example, a match with the score 6-3 3-6 6-4 equals 51.6% of total points won in favour of the winner, which indicates that a difference between winning and losing was only 3.2% of points won. Moreover, in this type of match, the average number of points played is 190, where 3.2% represent 6 points, which implies that by winning only 3 extra points the score could get even. In very close matches, the difference between victory and defeat can be as low as 2% of the points won. With that in mind, the “other” 30-35% of the points played within the category of 5-8 and 9+ shots can be very crucial, and no one can afford the luxury of being less skilled in those elements. With those small winning margins taken into consideration, the fact that 70% of the points finish in the first 4 shots and 30% in 5+ shots appear to be less significant.

2. BEST PLAYERS ARE EQUALLY SUCCESSFUL IN ALL TYPES OF RALLIES

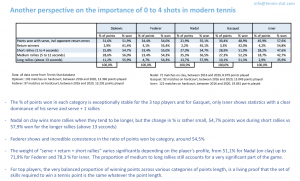

In collaboration with Tennis stats, we made a data analysis of the world’s best players on the sample of approx. 100 hard court matches for each player in the last four seasons, as well as 70 clay court matches of Nadal in the same period. The data in the table below show that the percentage of points won in each category is exceptionally stable for all four players, while only Isner shows a clear dominance of his serve and serve + 1 rallies.

According to these data, the best players in the world have almost the same winning percentages in all types of rallies. Only extreme examples like John Isner show the difference in performance between long and short rallies. This supports a strong argument that the set of skills required to win the short rally, is the same set of skills that’s required to win any type of rally, with exception of the serve. Good shot quality is a good shot quality regardless of the length of the points. In general, best players cannot afford to be less skilled in any type of rallies because, even the two-percent drop in performance in any type of rally will result in a significant difference in the final score. Finally, if a player is weaker in longer rallies, they either need to be extremely dominant with the serve or will likely lose the match. Due to the nature of the modern tennis, it is very difficult to rely exclusively on the serve and therefore there are not many players today that are extremely dominant on their serve.

3. POWER OF BASICS

I want to explain the theory behind the numbers that will clarify why all the best players are equally successful in all rally types. It’s very simple: the shot that will make a difference in the middle of the rally or at the end of the rally is the same shot that will give you advantage in the first shot after the serve. Djokovic’s backhand, for example, has the exact same technical qualities when played immediately after the serve or in the longer rallies. In addition, regardless of how much I believe in the importance of the return, a shot that gives you dominance in the longer rallies is the same shot that will make a difference on your return. The only shot that stands out, and is not connected in any way with the rest of the shots, is the serve. Serve is a special shot that requires a lot of extra time and attention, and it has been treated that way for decades.

The biggest argument is headed towards the return, and it’s about how much return really differs from the ground strokes. How many times have you seen a ground stroke that performs well on all surfaces, and is bad at the return? It’s possible, but it’s not very common. Even though ground stroke and return appear to be two different shots, in fact they are very closely connected. It’s not exactly the same shot from the technical perspective, although if you have a great ground stroke there is a big chance you will have a great return, too. Best players in the world are good examples.

This theory closely correlates with a sampling period in the development process of a young athlete. If you develop a wide range of basic skills at the early age, it gives you an advantage in the long run, and it’s easy to adapt to any specific sport later on. It is the same in tennis, if you develop a strong base on the forehand and backhand, it can easily be adjusted to a shot like the return. In other words, if you can teach a player great forehand and backhand (without any extreme technical elements, like grip for example), there is a great probability that they will develop a great return later on, as well.

However, we cannot say the same the other way around, because there are many players with a good return that struggle with their ground strokes in the rally, especially when they have to take control of the point or hit a winner. An effective return can largely depend on timing and using the pace of the serve, while at same time players are not really hitting the ball. The ability to control the point and hit a winner is something way more difficult to learn later in your career. That being said, the players must develop a strong basic set of skills that can later be adjusted to any specific situation on the court. Good ground strokes are the basis for good return, return+1 and serve+1. There is a sensitive learning phase for each element of the game, but especially for great ground strokes, and once the train leaves the station it is very hard to jump back in during the later stages in career.

4. TENNIS IS A GAME THAT STRETCHES FAR BEYOND NUMBERS

Lastly and most importantly, the crucial things happening on the tennis court are usually hard to measure. For example: if the player feels the struggle to win a long rally against the opponent, their natural reaction and only option is to try to finish the point as soon as possible, preferably in the first two shots. This will force the player to play faster than usual, which will inevitably lead to more unforced errors at precisely those first two shots. The stats for those particular points will put a check mark in favour of the opponent’s 0-4 shot game (because he really did win those points in the 0-4 game), while the truth is, in fact, the complete opposite. The quality of the opponent’s game in the longer rallies actually forced the player to make more mistakes in the first two shots. The pressure that the opponent made on the player with the consistency in the longer rallies actually generated better statistical data in the 0-4 category for the opponent.

Summary:

- 30-35% of the points played in the category from 5+ shots and above is a very significant amount of points, especially when we know that the difference between winning and losing a tennis match is very rarely bigger than 8% of the total points won. Players simply cannot afford being less skilled in any type of rallies.

- Recent data show that the best players are equally successful in all types of rallies. Skill set required to win a tennis point is the same for all rally lengths.

- Power of basics – the shot that makes a difference in the middle of the rally or at the end of the rally is the same shot that gives you advantage in the first shot after the serve. If you can teach a player great forehand and backhand, there is a big probability that they will develop a great return later on, as well. Good ground strokes are the basis for good return, return + 1 and serve + 1.

- Crucial things in tennis are hard to measure. Dominance in the medium and longer rallies makes a big difference in the short rally numbers.

Due to the complexity of the game itself, the tennis practice has evolved through the years into one of the most sophisticated sports training programmes in the world. My objective in this article was not to neglect the importance of the 0-4 shot theory in any case, in fact the work of experts in that field contributed a lot to the evolution of tennis coaching, and I truly appreciate that. I decided to challenge the theory mostly because of the misconceptions towards the practice court, according to which endless “grinding” and consistency are seen as a waste of time. I think that “grinding” was just a misused word in this case, and that, in “real life”, it actually means practicing the basics. We should not forget that every complex choreography is based on a simple basic step. All game patterns in tennis largely depend on the quality of the basic shots. Tennis players need to practice the basic technical elements every day. It’s an ongoing and continuously changing process, therefore it requires everyday training.

My intention is to support the coaches that believe in the power of basics and encourage them to keep believing in their work. Being very familiar with the general profile of tennis coaches, I’m sure we all think deeply about the best methods for helping our players, and when you feel that your players need to “grind” on the practice court, then, by all means, make them “grind”. Hitting a good backhand down the line in the right spot during a big point takes years of dedicated repetitions. There is no doubt that the first two shots are very important part of the game, however tennis is far more than just two shots; it always has been, and it always will be!

Follow me on social media: Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and Linkedin